In the weeks following the Kill La Kill (KLK) finale, I’ve seen a lot of people weighing in on the show. Given it’s popularity, over-the-top theatrics, and symbol-heavy plus textually-dense narrative, this isn’t anything too surprising. I really liked the show, and it’s inspired a lot of really cool discussion around the anisphere. People generally have a wide range of opinions on any given show, and it’s been fun seeing all the different ways people have experienced KLK.

That said, I’ve heard a lot of refrains that have been bothering me a little bit, which go like:

- “Tengen Toppa Gurren Lagann (TTGL) was just done better…”

- “I couldn’t really relate to the characters, so I just never got into the story…”

- “The show was thematically incoherent, so I’m not sure what was the point…”

- “It was really entertaining, but I didn’t feel emotionally invested…”

And so on. All of these are taken as criticisms of the show and are viewed as negative qualities. Now, I’m not going to debate that they can’t be taken as (very valid) criticisms of the show, because they can. However, criticisms have to come from somewhere, and it is my belief that there is a big difference between critiquing a show from what you want it to be vs. what it wants to be. And, in my opinion, this difference is key in teasing out how exactly we should be looking at KLK. I feel like many people have been viewing the show colored by beliefs that this was supposed to be similar to FLCL or TTGL, with a central, tight narrative centered around a “coming of age” story that deals with all the issues of growing up (through high school fights and saving the world from total destruction, of course), when in reality this is not what the show intends.

Instead, I think the show is trying for something different, and thus should be viewed quite differently. Instead of being thematically centered around the “coming of age” narrative, it instead uses the coming of age story as a vehicle for other ideas and social commentary. Instead, KLK should be viewed as more like a superhero movie that is a cross between TTGL, FLCL, and some of Imaishi‘s more recent works like Dead Leaves and Panty & Stocking with Garterbelt (PSG). This key distinction, which I believe KLK actually tries to make clear, then fundamentally changes how we should be viewing (and consequently judging) the show.

So: what is KLK, and what is it trying to say?

Note: This is by far my longest post, clocking in at ~8500 words. I’ve tried to keep everything clear and coherent, but as you can imagine with anything this length things can get messy.

Before I get to KLK though, let’s talk a little bit about criticism, since it really matters here.

Note: I might use the terms {show, story, text} and {interpretation, reading, criticism} interchangeably. Hopefully it’s not too confusing.

Critiquing Criticism

From what I’ve seen so far, I’d say most criticism can be divided into two categories: “subjective” and “objective”. “Subjective” criticism is when people interpret (and consequently critique) a show based on what they want to view it as, regardless of what the show seems to be trying to portray itself as. You throw away unnecessary information and focus on the reading that is most relevant to you. As an example, let’s take Naruto. To one person, the story be a narrative about social acceptance; to another, it’s really about the difficulty of dealing with talent; to another, it’s the difficulties of becoming an adult; to another, it’s a story about overcoming loss; to another, it’s a story about the meaning and value of friendship; to another, it’s about ancestry and familial/societal duties. Although it’s a typical “coming of age” story, many dedicated fans come away with very different viewpoints on what the story actually means.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with viewing a show this way, because this is how people derive meaning from what they consume: we feel connected to the narrative, get in touch with ourselves, and explore new ideas. In the process, we continually try to incorporate what we’ve learned and “better” ourselves as individuals. This is a beautiful thing that everyone does. However, when critiquing something from this viewpoint (or, alternately, trying to recommend a story to someone else), this type of reading can pose problems. What if someone feels differently than you about how to view a show? Then maybe the elements you thought worked really well and that make a lot of sense to him were wasteful and annoying. Maybe you even had polar opposite readings, which can often happen when dealing with themes like “effort vs. talent”: is X element a defense of hard work and persistence in the face of adversity, or a cynical commentary on how to get used to the fact that there will always be people better than you? Or was the real point that you should attempt to go beyond this simple dichotomy in the first place and start looking somewhere else? While this type of reading is fine for personal fulfillment, it tends to pose problems when discussing stories with others.

This inherent problem with subjectivity motivates a move towards “finding common ground”, and is the basis for “objective” criticism. Objective criticism, in it’s most basic form, assumes that this ground must exist somewhere. It moves the discussion from reading shows based on how you want them to be viewed and tries to view shows based on how they should be viewed. These two viewpoints are not mutually opposed to each other. Since we each exhibit biases in how we view things, true objectivity is a myth; on the other hand, there is usually some basis in the show for how people tend to view them (people tend to latch onto things rather than fabricating whole narratives outright), and so you can’t disregard those either. Objective criticism then seeks a way to combine these two elements together, taking the small “snippets” that people latch onto and build them up into some overarching consistent framework. The project of building this framework then starts to become more systematic: look at all the elements in a show and how they work together and try to use them to build up a model for how we should be looking at things. After you’ve established this common ground that people can agree upon (because anyone can do this and argue about how it’s done), you’ve established some grounds for objectivity.

The question, however, then becomes how to view such a project. Or, in other words, how much information you should be using to build up this “objective” reading. Are you limited to information about the internal story, such as the events that take place and the characters themselves? Or can you broaden your purview to include the “text” itself (aesthetics, dialogue/writing, etc.)? How does symbolism and imagery relate to “themes” or overarching motifs? And can/should you try and incorporate authorial “intent” into this framework? And so on.

How people answer these questions determine how they wish to construct such a framework. For some, these questions are fundamentally answerable, and really come down to questions of “taste”. As you can’t really “draw a line” between what should inform a reading and what shouldn’t (including emotional engagement and other personal biases!), you shouldn’t try to. According to this “subjectively objective” view of criticism, since we can’t really come up with an ultimate objective set of values to inform these “objective” frameworks, all readings and critiques become somewhat equally valid.

However, most don’t see this fundamental failure to construct an objective set of values as a fundamental failing of criticism that makes all readings equal. Instead, this is just another manifestation of the inherent unattainable nature of objectivity — we can still forge forward by doing our best to be objective, which just means we just have to establish some set of values that we can all agree upon as “fair” interpretation. Unfortunately for these “strictly objective” critics, establishing such a set of values is far from easy, as we each have our set set of biases that tends to color our judgments (for instance, I tend to be biased towards the “abstract” in media, which affects how I perceive shows).

This failure to come to a consensus on values — on how much “the consumer”, “the producer”, and “the text” play into any given reading and how they all work together — is by far the biggest source of disagreement between criticisms of the same show. Often, critics fully agree on the elements actually present in each show and what they’re meant to be interpreted as — the problem is ultimately judging how well the show does at delivering on these things.

Besides a failure to agree on a core set of values, there are other pitfalls to this type of methodology. The biggest one is the risk of over-interpreting things: once it becomes permissible to use outside information to try and put a show in context (as well as a wider array of elements within a show), you run the risk of again reading your own narratives into the show. For (somewhat) recent examples where anime bloggers might be guilty of this sort of thing, we can look to discussions on the new Eva 3.0 movie, light novel (LN) adaptations, and Nisekoi. This type of thing becomes particularly problematic in a show as textually complex as KLK, which will come up later.

Before continuing, I want to point out one thing: these types of interpretive stances are more than just abstract theories, but also ways in which fans interact with media. This whole discussion about what quantifies criticism is both important as an abstract debate, but also because it determines how much you enjoy shows. As fans, our viewpoints and tastes color what we watch and how we receive it. And if a show seems to be in conflict with some of our personal biases, we don’t really like it. There are two ways around this sort of dilemma: go the route of the “subjective” critic so that the show becomes what you want, or change your point of view so you can watch the show on its own terms. I’m not advocating for either (because everyone is somewhat entitled to feel how they want about what they consume), but just pointing out that these types of thinking can have major impacts on how we view things. For me personally, I’ve found that following the latter piece of advice has led me to enjoy more media (as a “fan”) while also becoming more critical of it (as an “critic”).

I also really want to emphasize that I’m not telling you how to watch anime. Everyone is entitled to consume media however they want, and there is no intrinsic “better” way to do things when it comes to trying to watch anime. As Froggykun has recently argued, there is no such thing as an “elitist” anime – it’s an entirely a socially constructed ideal. Similarly, when looking at and criticizing shows, you’re justified in having whatever opinion you want, because it all depends on what you actually want when you’re criticizing a show. This isn’t meant to be a “STAHP GUYZ UR DOING IT WRONG” type of post, even though it could easily be read that way. Instead, what I’m saying is that if you believe in some idea like “objectivity” in criticism, you should try and do your best to make sure enough people can understand where you’re coming from. And hopefully, even though everyone has their own biases, you can come up with a framework that people can agree on so you can look at shows from a similar perspective: at least getting a consensus on the elements present in a show and how they work together, even if you end up disagreeing with someone else how you feel about them. That’s always a good thing to strive for, right?

In ∑: Even though you can’t really be completely objective when you critique something, if you like the idea then you should still try because it matters.

Advocating for a “Fair” Way to Criticize

All this aside, however, I think that there is a way forward for the strictly objective critics – there, in essence, a “best” (or “fairest”, whichever you prefer) interpretation for any given text. Here’s my attempt to define this:

An interpretation that incorporates the most information from/about a text into a coherent, falsifiable narrative using the fewest assumptions (relative to other interpretations) is the “best” interpretation.

There are several elements to this definition that are important:

- Coherency: the interpretation has to make sense, even if that “making sense” is “the themes are meant to be disparate and unrelated to each other”. If it doesn’t, then it doesn’t qualify as a useful interpretation.

- Falsifiability: the interpretation needs to have an inherent possibility to be proven false. It is first and foremost an argument, whose details can be argued for or against and which can ultimately be disproved given more evidence.

- For instance, if I use psychoanalysis to claim that Neon Genesis Evangelion (Eva) is really all about sex by turning most of the show into phallic symbols, that’s a reading that is actually non-falsifiable: as the Oedipus complex is seeks to deny itself, any refutation of this reading in fact proves the existence of the Oedipus complex and henceforth actually supports it (wait what?).

- Or if I use historical materialism to construct a narrative about how TTGL is really about the subjugation of the proletariat and the revolution of the working class against the bourgeoisie, you can’t really falsify that either: it’s a meta-narrative that can read itself into almost any story.

- Heavy usage of Christian symbolism in readings frequently are also non-falsifiable because of the ubiquity of certain symbols/elements (OMG JESUS FIGURE) across many narratives and cultures and the wide assortment of themes with some sort of Biblical ties. Note that this isn’t meant to discredit the use of religious symbols in any readings (I’m going to be using some later, for instance), but rather to point out that you need to be really careful when using really broad symbols to interpret texts.

- Simplicity: the interpretation needs to incorporate all the information together with the fewest assumptions and logical leaps, much like Occam’s razor. While some are always a given when interpreting texts, all logical progressions that exist should be well argued and supported by the text as much as possible. The best interpretation will do this better than any other competing interpretation.

- Nowhere here do is there a limit on what information surrounding the text you can bring in – I believe that the best interpretation should be able to include as much information as possible, regardless of direct relevance. Interviews, historical events, symbolism, characters, dialogue, color scheme: the best interpretation should be able to include them all in some way, shape, or form (or at least deal with them).

- In other words, this is just another way of saying that criticism should include all available elements, including form, content, and things that can inform that content. This definition thus inherently takes a stance on how we can answer those questions above: rather than retreating from their subjectivity, as the subjectively objective critics do, this view instead embraces it, and requires our interpretation to take this into account.

- This then leads into another point about falsifiability: the whole system upon which this “best” interpretation is structured can (and should) also be debated. By doing so, we can improve both the methodology and interpretation itself!

All these definitions work together and enable each other to create the “best” interpretation. Now, I’m not going to deny that there’s a lot of “bleed-over” in this definition from similar ideas in physics and the sciences on what in general classifies the “best” working theory (and which I am heavily influenced by), and there are problems with it there too (like debates surrounding the anthropic principle). However, I think that it’s a pretty good place to start if you want to treat criticism and interpretation a little bit more objectively and and establish some sort of “fair” criticism.

In ∑: My idea of what constitutes the “fairest” critique is one that most easily makes the most sense out of the most things without being impenetrable bullshit.

Building Up a Mindset for How to Go About Viewing Kill La Kill

Alright. So now that I’ve built that up, let’s talk about KLK, because there’s a lot going on that we need to make sense of, including but not limited to:

- Puns and wordplay. which characterize everything from the main plot points and naming scheme to Mako’s antics.

- Very good use of visuals, such as creative uses of still frames and associating characters with visual gags/elements, such as Nui.

- Extremely reference heavy, with a lot of visual gags referring to older shows and past work.

- Extensive amounts of nudity, which seem to be associated with female empowerment and/or exploitation.

- Strong ties to a “coming of age” narrative.

- Heavy use of thematic symbols, including stars, wedding dresses, blood, etc.

- Subversion of a lot of things: of the shounen paradigm, of high/low art, of hierarchies, etc.

- By the same token, a heavy emphasis of those very hierarchies through things like environments.

- Intensely “over-the-top”, ridiculous, and all over the place.

- Extensive references to/re-purposing of history and mythology. (I will elaborate on these later.)

- Numerous points of social commentary.

And I’m almost certain I’ve missed a lot of stuff. As the links show, these wide variety of elements have led to very different readings of the show. Many of them aren’t mutually contradictory, but many of them seem disconnected, instead focusing on specific elements in the show rather than trying to incorporate many of them as a whole.

But I didn’t intend to come into this debate to pick a side. Instead, I want to ask the question:

What is Kill La Kill actually trying to say? How does the show want to be read?

I think the answer to this question finally leads to a resolution to two of the biggest problems I’ve had with most readings of the show:

- They don’t incorporate many of the historical/mythological/religious references. Why are they in the show in the first place? The anime references can be chalked up to self-parody and/or genre subversion, but it’s difficult to justify the use of these other elements that aren’t explicitly grounded in the anime industry. (Again, I will get into more of these later.)

- Nui. In almost every reading I’ve seen (minus the feminist ones), she is a non-entity. Why the hell is she a character in the show? Ragyo is plenty scary enough and already had a willing aid (Hououmaru), so why did they include the Grand Courtier? And why portray her as they did, as a hyper-feminine, super-cartoony version of essentially chaos incarnate?

For both of these, I’m assuming there’s some deeper meaning besides “Let’s use some mythology!” or “Ryuko and Satsuki need an antagonist their age and let’s make her terrifying!” type of argument. Imaishi, Nakashima, and company have almost free reign to do what they want in these episodes. Given that evidence seems to point to them planning ahead, I’m tempted to give them the benefit of the doubt.

In ∑: People have a lot of different ideas about what KLK means since it has a lot going on, but we should be asking what KLK wants to showcase itself as rather than how exactly it can be read.

What is Kill La Kill Trying to Say About Itself?

Given my long tangent on criticism and trying to figure out what a show wants to be seen as (rather than what we are tempted to see it as), how should we be looking at KLK? I think the final episode is a good place to start, because it actually drops most of the shows pretenses (wait the show had pretenses?!) and fires out random nonsense all over the place. In looking at the final episode, I’m going to try and do as little analysis as possible, except bringing in some more obvious concepts from the previous episodes as they are again re-introduced and put on display. By doing so, I want to let the show speak for itself, and do as little analysis as possible. I want to inject as little of my own pre-conceptions into what I’m seeing, except when necessary, and draw conclusions based on what I see rather than what I want to see. It’s a difficult line to draw sometimes, but I’ll try and do the best I can.

Note that most of the conclusions I draw from the show in the finale work when viewed in the rest of the show, but I want to just stick with the finale and see where it takes us…

First, let’s look at Ragyo: how is she portrayed in the final episode?

Ragyo is repeated related to Christian imagery, and in addition is displayed as an absolute authority figure who promises pleasure in exchange for freedom (also seen in the whole “Junketsu dominating Ryuko” arc). This has been a running theme throughout the show, and Ryuko and company must resist such a call: they must fight for their emancipation from such a monster.

How about Nui?

Nui looks almost psychotic here as she tries to defend the transmitter, and is literally all over the place both on screen (in how she’s animated) as well as in the show (through her many life fiber copies).

However, she’s also shown as exquisitely feminine and submissive when she willingly takes her own life for her “mother” (notice all the pink and hearts).

So Nui represents a few elements here, including anarchy/chaos (both in the show and on-screen), submission, and femininity (all that French feeds into this “refined” image). Plus she is emphasized again as being exquisitely non-human, as is Ragyo. Notice that Ryuko and company must not only fight off Ragyo, who symbolizes absolute authority, but also Nui, who symbolizes complete anarchy.

How about the other elements in the final episode? First, let’s look at some of the more comic scenes.

So we have a show that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

Second, we can look at scenes that reference other anime. The final episode’s chock-full of references to previous shows, most notably to TTGL, Eva, Gunbuster, and Dragonball. (Although there are a lot of others here as well.)

So again we have this collage of previous stuff that’s archetypical of both previous Gainax work as well as shounen in general.

But there’s one more element to note here, and that’s the meta-awareness the show embodies by breaking the fourth wall.

So, in sum, we have a show that is chock full of references smashed together into a cohesive whole, constantly ribs itself, and also is very meta about everything it’s doing. Given that almost every main event in the show has been a repurposed archetype from the shounen genre or a smorgasbord of other influences, I’m hesitant to take any element of the show at face value at this point!

But wait: I’ve skated past our main duo! How do Senketsu and Ryuko fit into all of this?

We have Ryuko and Senketsu standing as substitutes for mankind’s ability to evolve and take on new challenges, in an almost exact repeat of TTGL. Ryuko and Senketsu take their places among the ranks of Simon and friends as they fight for the human race, essentially fulfilling shounen archetypes (but in re-purposeful way!).

But what else do they do?

Again, we have two things at work. First, is the standard “ridiculous speech stating the obvious” that occurs in most shounen showdowns. But it’s been re-purposed for more than that here. Instead, we’re coming back to a big theme of the show: tearing down dichotomies and barriers by subverting them. It’s also a great way of stating that we are both what we appear to be and yet more than that, and the ways that clothing both defines and yet does not define us. As clothing has been an important element of the show (most prominently, a symbol of oppression and conformity through wedding dresses, school uniforms, etc., rather than an expression of individualism), this seems to be a pretty big call to again resist such types of oppression. Again, I’m seeing more things related to resisting oppression, which I think is more than just me reading themes into the show…

Speaking of clothing and oppression, the post-fight scene is quite interesting…

I think, out of everything in the final episode, here is where KLK finally drops everything and just speaks its mind. This scene is encompasses two of the main features about the show: it’s “coming of age” narrative and its heavy dose of social commentary (especially concerning themes of emancipation and resistance against authority).

BUT THAT’S NOT ALL.

We see a re-emergence of family as important, even though both Ryuko and Satsuki have been freed from familial duty (remember, Ryuko originally began wanting to avenge the murder of her dad but eventually moves beyond that). We are again shown that the sometimes oppressive nature of legacies and families can be overcome through the search of love and equality. I don’t think that’s too much of a stretch.

There’s also one more element that bears consideration.

There’s not that much explicitly said about growing up through the show — this might actually be the only line. So it bears consideration that it’s a statement about duty and responsibility given power. It’s a cliche (like everything in the show), but it’s a good one: with power comes responsibility. And that responsibility is to not to be a dick and oppress people but instead do your best to help others as equals. Because everyone’s equal when they’re naked!

Combining this, we get a reading like this:

(In a meta-aware, non-serious yet somehow authentic way) Ryuko/Senketsu (as reference-filled reincarnations of TTGL protagonists) defeat Ragyo (God/Satan/oppression/promise of pleasure in exchange for subservience) and Nui (chaos/anarchy/femininity/submission) while delivering social commentary about the desire for resistance/emancipation (through the oppressive nature of clothes/femininity and familial duties), the duties of adults/growing up (through nudity), and the desire to love one another in spite of everything (through Ryuko and Satsuki’s reunion).

This is a pretty cool thing that simultaneously fits in with a lot of other readings (destroying hierarchies, power of friendship, female empowerment, etc.). Note though what we don’t get out of this. We don’t get a lot of discussion about growing up: indeed, that doesn’t even seem to be the focus of the show, unlike TTGL. Instead, we see that the majority of the final episode as used as a vehicle for other means. This is a fundamental shift in how we are viewing the show: unlike TTGL or FLCL, where the coming of age story is seen as the primary focus that everything is built up around, in KLK it is instead a vehicle for other ideas!

In ∑: Looking at KLK more closely, a combination of elements seem to indicate that we should shift our focus: the show should be viewed as a coming of age story that serves as a vehicle for other ideas rather than ideas becoming synthesized into a coming of age story.

De-Emphasizing the “Coming of Age” Narrative: Broadening Our Scope

In the beginning, I pointed out several problems I had with current readings of KLK. The first couple concerned difficulties in incorporating historical/mythical information as well as Nui’s character into the readings, while the rest mostly involved me feeling uncomfortable that some of the critiques of KLK were justified (like not being able to “relate” to the characters). How does this new focus outside of the coming of age narrative solve some of these problems?

First, a lot of the discussion around KLK‘s heritage has noted that it pays homage to a lot of Gainax’s stuff. And most of these references are to Gainax’s really well known (and extremely well-done) “coming of age” stories, from Eva to FLCL to TTGL. Given that Imaishi and Nakashima were also the main duo behind much of TTGL (and the former’s heavy involvement in/influence from much of the former), and the fact that KLK also spends a lot of time making references to elements from these shows, this comparison is quite apt. However, by focusing on the Gainax-influenced aspects of the show, we miss a good chunk of other material that might be important to viewing KLK. Such as what Imaishi has done outside of TTGL.

Once we look at Imaishi’s other directorial work where he’s been given a lot of free reign to go wild, we start getting a different picture. Look at the craziness of Dead Leaves - is there anything relateable about the characters there (or the essentially nonsensical plot)? How about the OVA’s obsession with these two rogues demolishing everything to the ground?

Or PSG, which has a lot of parallels to Dead Leaves. Like the main duo’s names, Panty/Stocking vs. Pandy/Retro, or it’s intensely “crass” nature, or it’s crazy antics. Are Panty or Stocking “relateable” (and is that even a downside to this show)? Isn’t there an entire episode segment dedicated to song where the chorus is “ANARCHY“? Aren’t those also the surnames of the main characters?! How about the fact that, like TTGL (and KLK), it’s stuffed to the brim with references to other works? Doesn’t it actually deliver a decent amount of incisive commentary on pop culture and anime in general?

Or how about Inferno Cop? There’s a lot of crudeness there too, which also seems to work towards the series benefit. And a lot of “bringing together tropes to lampoon them but also make a ridiculous over-the-top story”. And a lot of craziness. And themes of anarchism.

There’s definitely a trend here, and it’s one that others also have noticed: Imaishi loves making shows which prominently feature “anarchy” as a leading refrain, for better or for worse. Many of these shows are themselves pastiche, honoring the genre(s) by cramming in as many references and styles as it can while at the same time poking fun at itself. And, in their most recent incarnation, you see these themes reappear in shows like PSG coupled with signs of social commentary and impulses towards ideas of emancipation.

This gives us a new way of looking at KLK: as the latest incarnation of Imaishi’s emphasis on motifs of resistance/emancipation that begins with something like Dead Leaves and ends with PSG and KLK. Hell, this also gives us a new way of looking at the overriding conflict in TTGL, which actually echoes these very same things.

So what does this have to do with KLK‘s “unrelateable” characters or “scattershot” themes?

Let’s go back and look at some of Imaishi’s recent work like Inferno Cop and PSG. While both of these include a lot of references, it’s important to note where these references are coming from: Western media, ranging from children’s cartoons to superhero stories. Why is this relevant? Because look at the main characters of many of these stories, from The Powerpuff Girls to Superman: are they relatable? NO – many protagonists of Western cartoons are in fact not relatable at all! We can’t really connect with Superman, invincible superhero, or Batman, ultra-rich billionaire vigilante. While the movies go to great lengths to humanize these heroes so we understand that they’re people and can root for them, we’re oftentimes there to watch the spectacle. This situation is even more prevalent in children’s cartoons or old-fashioned comics (think like pre-Watchmen type stuff), where the whole point is to enjoy the spectacle. Are these all points against them being good? For me at least, they aren’t necessarily, although preferences might change.

However, this does give a way that we might want to be looking at the protagonists: more akin to “gods” or “superheroes” (modern mythology in action!). If we’re supposed to be viewing the show as more of a superhero series, then the fact that we can’t really relate to the characters isn’t really a bad thing. The show tries to make us see them as people, but that’s really the only important bit. We don’t need to empathize with the characters, but instead the conflicts they represent. This is at the core of most superhero movies I see today, and probably is a big way that Western influence might have had a hand in KLK.

If we now look at this central conflict, we also gain a new way of looking at the “themes” of the show and understanding why they appear to be so “scattershot”. Normally, in traditional narratives, themes are like arguments who are given their strength through the story itself. For instance, a resounding theme in most “coming of age” stories is the “loss of innocence“. This is often articulated in ways where the main character must learn to comprehend and face the difficulties of the world around them. These are illustrated by breaking down simple black/white formulations of morality, having characters encounter failure, and a host of other influences. As experience is always a better “argument” than something written down, stories help showcase these ideas by “bringing them to life” so we can experience them for ourselves. Looking at themes this way frames the question in terms of an argument: how well does a story get across it’s main message? Are the conclusions justified from the experiences? Is it nuanced enough? Did they resonate with me on an emotional level? And so on and so forth.

But what happens when this idea breaks down — when the “coming of age” narrative is no longer meant to illustrate these themes, but instead serves as a vehicle to deliver a host of separate ones? Themes then no longer can be arguments illustrated by the story, but rather should be seen as argumentative thrusts, ideological impulses characterized by overriding mentality. Indeed, fleshing them out isn’t even the point (although it can be if the piece of media is centered around specific social critiques). In this view, themes in and of themselves are less important than the impulses that drive them. They become stabs at society, commentary meant to raise awareness and exemplify an attitude or “call to action” rather than a fully-formed argument. And they should be evaluated on how well they do that (if that is their main intention), rather than how well they are argued!

In ∑: By shifting our focus from that of a typical “coming of age” story, KLK looks a lot more like a mix of PSG/TTGL than older Gainax shows: the characters are more like Western superheroes (that we often can’t relate to) and the themes are social commentary, both of which are united by ideas of resistance against authority that we do empathize with. Common critiques thus seem to come from a viewpoint contrary to how the show wants to be viewed.

The Drive for Emancipation against Oppression and Anarchy

So we now know what the overriding theme of KLK looks to be: emancipation. Resistance against structure, against duty, against history, against society, against self-imposed constraints (very reminiscent of critical theory). In my first real attempt to integrate things together in the show, for instance, I noticed many of these themes but tried to subsume them under the “coming of age” narrative. In short, I was guilty of reading KLK in the way I just described above (although I was a little bit less critical about it as others have since been)!

However, given this new idea that the main driving force of the show is not the “coming of age” narrative but instead this impulse for emancipation, what can we say about our original two issues (myth/historical motifs, placing Nui in the story)? Nui actually turns out to be pretty easy – the key is the fact that she fits into a “the evil specter of feminism that Ryuko must defeat!” really well. This reading — one of the only ones that actually uses Nui’s character properly — works because Nui is transformed into a symbolic/ideological oppressor that must be defeated. Let’s take this idea and apply it to her whole character.

In most of Imaishi’s work, there’s this active chorus of anarchism as a way to resist oppression, and we see that present in KLK in spades. Given what we know from the final episode, I’d say it isn’t too much of a stretch to associate Ragyo with the specter of absolute dominance and authority. But is the natural opposition to authority anarchism? The answer is probably no, because complete anarchy is about the same as complete dominance: no order at all is in fact another form of submission that gives up on any hope of order in the first place and submitting yourself to utter chaos. Although it is a tempting choice in the fight against authority, it is not actually the one you should take. Nui’s character then can be framed in a context where she is the other end of the dichotomy that must be opposed: you must resist both absolute authority and absolute non-authority because they are both rob you of your agency. In the quest for emancipation, one must constantly fight against both extremes, and so Nui’s character is both a symbol of feminism and anarchy that must be actively opposed.

In ∑: By focusing on the underlying push for emancipation, we can extend Nui’s symbolic role as oppressive femininity to oppressive anarchy that must be opposed along with oppressive authority.

Unification, State Shinto, WWII, and Oni: Overtures to Historical/Mythical Japan

But how exactly can you do this? How can you fight against both authority and anarchy? Well, here’s where a little bit of history enters into the picture.

Note that large swaths of this section were informed by a panel at Anime Boston 2014 by Charles Dunbar and Katriel (Kit), so most of these ideas were originally theirs and they deserve full credit!

The Unification of Japan

KLK bears some noticeable parallels to the times of Oda Nobunaga, first and foremost with Honnouji Academy.

The names, like most things in the show, are puns using almost exactly the same characters with very different meanings. Note also that Honnouji is the end of Satsuki’s ambition, and where the final showdown takes place that essentially “burns” the building to the ground. Taken from http://art-eater.com/2013/11/kill-la-kill-the-fashion-of-fascism/.

But we also see parallels between Nobunaga’s conquest to unify Japan and Satsuki’s plan to conquer all high schools. Nobunaga, over the course of his lifetime, managed to unify central Japan. His conquests were centered on the Kansai region and marked by intense brutality (especially against religious establishments). His catchphrase was “Tenka Fubu [天下布武]” (tr. “all under heaven through military might”), which symbolizes his use of violence as a tool to unify the continent. In a “I’m pretty sure this is intentional” parallel, Satsuki too aims to conquer this very same region of Japan in her Tri-City Raid campaign.

Notice that Osaka, Kyoto, and Kobe (right where “Settsu” is), are smack dab in the middle of Nobunaga’s conquest.

Both of the main “Unifiers” (Nobunaga and his successor Totoyomi Hideyoshi) undertook large projects to centralize government, and enacted social policies designed to increase their political power. Nobunaga initiated land surveys that were later continued by Hideyoshi, both with the aim of establishing not only a survey of the realm, but more importantly their right and power to tax. Through this system, they established a coherent census and system of income while also flexing their military might. In addition, both Unifiers engaged in so-called “sword hunts,” where they attempted to disarm the peasantry to ensure they had a monopoly on violence. Finally, Hideyoshi actually implement a Neo-Confucian “class” system in Japan and promulgated decrees preventing social mobility between then. These four main classes (samurai -> peasants -> artisans -> merchants) were at the heart of Japanese society, with the Emperor of course on top overseeing the whole shebang (and by “Emperor” we really mean the shogun, because they held all the real power).

But what do we see here?

There are noticeable differences of course (you can move around in Satsuki’s system, not so much in historical Japan), but the similarities are a little bit uncanny (why did they pick four levels, specifically, after the other historical parallels with Japan’s unification?).

The Rise of State Shinto

There are two interesting things to note here about the previous view:

- Satsuki is looking quite like a god-like figure who lords it over the school. If we take the “class” system as historical parallel, that seems to support this idea.

- Satsuki’s system looks really fascist and involves a centralization/monopoly on violence (through her Goku uniforms), very similar to those built up by the great Unifiers.

But Satsuki is more than just a God-like figure. Look at all the symbolic overtones present in the first episode, for example.

When Satsuki is first introduced, she stands as a radiant source of light from on high who shines down on those below.

Going with the image of a God-like figure in mind, why would Satsuki be so often linked to the Sun? (I’m assuming her dazzling radiance is more than just KLK being ridiculous.) Well, in Japan, there’s one Goddess that actually is literally the Sun in the Shinto pantheon: Amaterasu.

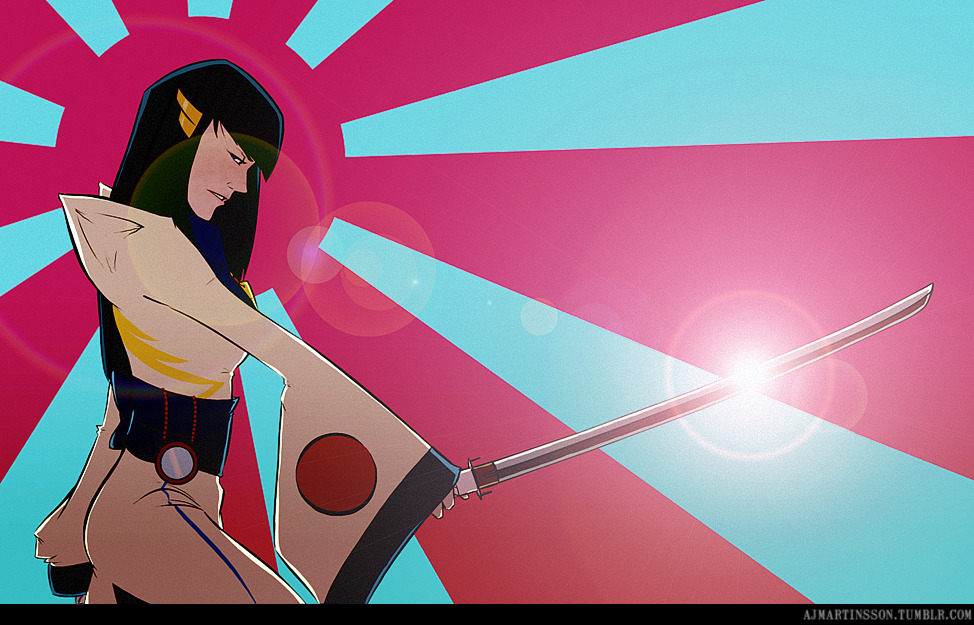

Satsuki re-envisioned as Amaterasu, Goddess of the Sun. Taken from: http://ajmartinsson.tumblr.com/post/80223870607/satsuki-kiryuin-from-kill-la-kill-re-imagined-as

So let’s just assume, as a starting point, that all the god-like overtures and symbols in the show have been pointing to Satsuki as a symbolic representation of Amaterasu. You can actually make a lot of cool parallels with certain events in the story and the “Elite Four” relating a good chunk of their personalities to Shinto deities (Jakazure = Ame-no-uzume; Gamagoori = Hachiman; Sanageyama = Susano-o; Inamuta = Izumo Okuninushi; and Mako is some deity I forget; email Charles or Kit for more info on this), but for my purposes relating Satsuki to Shinto at some level is enough, since it inspires the following question:

- How does Shinto and fascism go together?

The answer? As State Shinto, and ideology developed during the Meiji Restoration that placed the Emperor as descended from the divine (Amaterasu herself) that would bind the state of Japan together as it modernized and centralized. Under this ideology, the state essentially became a pseudo-fascist power.

What (partly) triggered the Meiji Restoration, and why/how did Japan modernize? It was mainly as a response to Western Imperialism, which forced Japan to finally end its long period of isolation from the West. Seeing how the West demolished China, Japan struggled to modernize as quickly as possible to prevent the same thing from happening to itself. Much of this modernization involved taking huge cues from Western powers as Japan essentially mimed the West to prevent being colonized by it, imbibing the ideas of their oppressor in order to resist them.

So now we have an analog for Satsuki and her system at Honnouji Academy as representative Meiji Japan.

The Imperialistic, Christian West

But what is she trying to resist, and who is she taking from? Luckily, the show answers our question for us.

So Satsuki was trying to beat Ragyo by imitating her. Could that make Ragyo…the West? This idea is not actually too far-fetched.

Ragyo is strongly linked to gross capitalism (both in ideology and in position as the head of REVOCS), often a symbol of the West.

Besides being strongly linked to capitalism, she essentially is imposing her own will on Satsuki, who then tries to imitate her to defeat her (much like Meiji Japan does to the West). She’s even more arrogant than Satsuki, looking down upon her daughter and all that she’s accomplished as inferior.

And, most importantly, if we make the same sort of claims over how she’s portrayed in the show relative to Satsuki, she’s pretty much God.

If you actually pay close attention though, it’s ONLY Ragyo who says these ideas – no one else makes such claims in the entire show. This is something I missed last time around, since it explicitly ties Christianity to her.

If the symbolic relationship is Satsuki = Sun -> Amaterasu, then by extension Ragyo = Rainbow -> God.

As rainbows are symbolic of a covenant between God and mankind, such symbolic language is fitting. Ragyo is making a promise that she reiterates multiple times throughout the show: sacrifice your freedom and I promise you unending pleasure in subservience.

Note: I also like the argument that because God’s so hella-badass he can’t be contained by just one color and so is a fucking rainbow, but the previous one makes more sense as I’m making an argument about symbols rather than colors.

World War II and the Occupation of Japan

Alright, so now we have Ragyo as the oppressive, dickish, imperialistic, Christian West that Satsuki has been trying to overpower. And about 2/3rds of the way through the series, Satsuki finally makes her move. She (i.e. now-unified Meiji Japan) rises up against her mother (i.e. the West).

Of course, this doesn’t end well — Satsuki is utterly demolished and her home fortress (i.e. Japan) is taken over (i.e. occupied) by her mother (i.e. the West) who starts running the show.

Again, here’s another overture about trying to use fascism to defeat a “fascist” oppressor. I’m seeing something in common with these historical parallels…

Oni and “Old” Japan

But where does our protagonist fit in? We’ve talked about the symbolic representation of pretty much every single other character except for Ryuko, who is the main protagonist against all this crap! If Satsuki represents modernizing/Shinto/fascist Japan and Ragyo is the imperialistic/Christian West, the most likely contrast is that Ryuko is neither of these: not modern and not foreign. In short, she’s “Old” Japan, the one that loses out in all this fighting.

This reading is not completely crazy though, and it actually has it’s basis in something I’ve been wondering about for quite some time.

During her transformation, why does Ryuko have horns? They’re a completely unnecessary part of the whole outfit and aren’t really tied to the clothes.

This little bit of innocuous information is a puzzle, and I think is the key to making sense of this reading, because there is one other Japanese icon famous for having horns: oni. Oni are yokai often associated with horns and righteous anger. In addition, the common usage is for those of “alien” origin, peripheral troublemakers outside the scope of the Emperor. Given Ryuko’s alien nature and her perpetual isolation throughout the narrative, as well as her righteous anger for the good first half of the show, I’d say she fits the bill quite nicely here.

A New History

So, the history of KLK seems to go something like this:

- Honnouji’s name and class system along with the Tri-City raid draw parallels to the unification of Japan and overt references to rising centralization and fascism.

- Satsuki bears strong resemblances to Amaterasu, which, combined with her connections to fascism at Honnouji place her as a representation of State Shinto and the Western-based modernizing (pseudo-fascist) project of Meiji Japan.

- Ragyo represents God and the West, which are strengthened through her interactions with Satsuki. She is also modeled as an oppressor.

- Parallels to WWII and the occupation of Japan are evident after Satsuki’s failed rebellion, another example of attempting to rebel against an oppressor by using the same methods of oppression.

- Ryuko represents “Old” Japan as an Oni, a member on the periphery filled with righteous anger who has lost out in all of this.

- At the end of the show, “Old” and “New” Japan realize unite against a common enemy, Ragyo (i.e. absolute oppression), in order to defend their freedom.

Almost all the historical references made in KLK are of eras of centralization and modernization, of government and authority growing larger and more violent as they impose their will on those of the populace, and of how much of this is justified in the face of looming threats. We thus arrive at an answer to our original question: How can you fight against both authority and anarchy? According to KLK, we can’t look towards repeating history — imitating the methods of the oppressor in order to fend them off is not the way to go.

So what can we do? What we’ve always done: love others like family, help them out when necessary, treat everybody as equals, and try and live your life the best you can.

And I think that’s the message KLK wants to drive home to us. That’s the reading that all the evidence seems to point to. And it might be simple, but I think that’s what makes KLK so great: using such amazing complexity to deliver an impassioned call for all of us to love one another.

![For soft power to work, nation [X] must possess some relationship to object (x). The exact nature of this relationship is unimportant - what matters is that it exists within the mind of a third part and that it means something to them.](http://eyeforaneyepiece.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/slide7.jpg?w=470&h=352)

![Then, another actor [Y] must engage with object (x). Note that it can't be to [X] directly - that would be too easy, and wouldn't really satisfy the definition of soft power that makes it "special".](http://eyeforaneyepiece.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/slide8.jpg?w=470&h=352)

![Now comes the most crucial step: this engagement with (x) must go beyond just the object itself and extend to the nation [X] with which (x) is related to. If this fails, then you really haven't exercised any real "power".](http://eyeforaneyepiece.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/slide9.jpg?w=470&h=352)